天下父母心 A Child Is Waiting(1963)

演员:

影评:

- 還是電影的英文原名《A Child is Waiting》更為貼題。智障、精神有問題的孩子,都在等待著父母的愛。

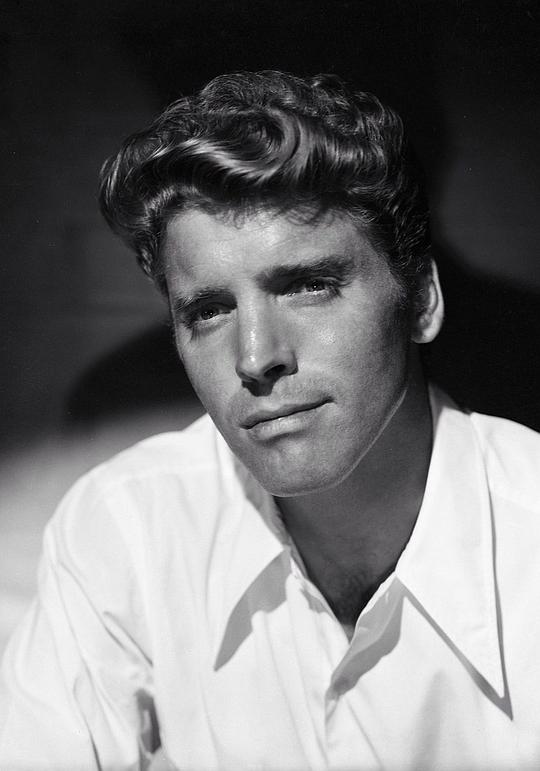

《父母心》是卡薩維蒂(John Cassavetes)早期的電影,此片並不是一部自主電影,相反是荷里活主流製作。女主角茱迪嘉蘭(Judy Garland)曾是歌舞片紅星,是《綠野仙蹤》裡的Dorothy,男主角畢蘭加士打(Burt Lancaster)是當年與馬龍白蘭度爭一日長短的一線猛男。監製找卡薩維蒂,本來是想要他拍部賺人熱淚的溫情片,但自主的卡薩維蒂不賣賬,把焦點放在孩子身上,結果茱迪嘉蘭還是演得太誇太浮,畢蘭加士打扮院長亦被他過份俊朗的容貌所累,缺了一份說服力,情況有點像劉德華。

卡薩維蒂的太太珍羅蘭絲(Gene Rowlands)在電影中飾演丟棄智障兒在醫院的母親,好心做壞事的茱迪嘉蘭騙他回醫院見兒子一面。初登大銀幕的羅蘭絲把「太愛兒子不願相見」的矛盾真情演得入本三分。卡薩維蒂大概一定也覺當時年青冷艷的太太和自己都比一眾荷里活明星更懂演戲,及後二十年都用她做女主角,自己也經常自任男主角,夫妻拍檔自主地拍電影。 Title: A Child Is Waiting

Year: 1963

Genre: Drama

Country: USA

Language: English

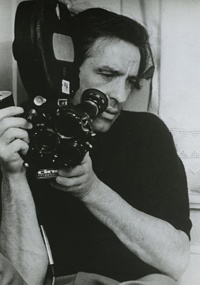

Director: John Cassavetes

Screenwriter: Abby Mann

Music: Ernest Gold

Cinematography: Joseph LaShelle

Editors: Gene Fowler Jr., Robert C. Jones

Cast:

Burt Lancaster

Judy Garland

Bruce Ritchey

Gena Rowlands

Steven Hill

Paul Stewart

Gloria McGehee

John Marley

Mario Gallo

Lawrence Tierney

Juanita Moore

Barbara Pepper

Elizabeth Wilson

Rating: 6.5/10

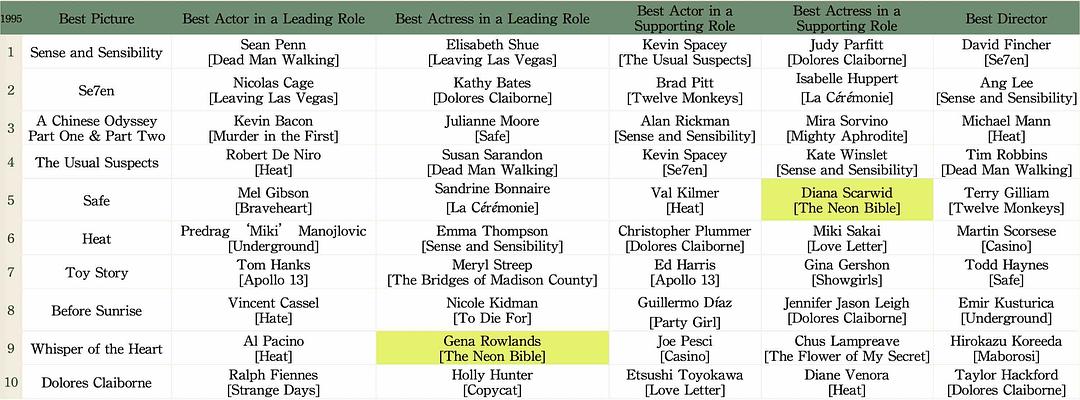

Title: The Neon Bible

Year: 1995

Genre: Drama

Country: UK, Spain

Language: English

Director/Screenwriter: Terence Davies

based on the novel by John Kennedy Toole

Music: Robert Lockhart

Cinematography: Michael Coulter

Editor: Charles Rees

Cast:

Gena Rowlands

Jacob Tierney

Diana Scarwid

Drake Bell

Denis Leary

Leo Burmester

Dana Seltzer

Frances Conroy

Bob Hannah

Tom Turbiville

Peter McRobbie

Rating: 7.4/10

To honor Gena Rowlands (1930-2024), the titan of performative art on the screen who departs us on 14 August after suffering from Alzheimer’s for over 5 years, here are her two lesser seen films. A CHILD IS WAITING commences her cinematic collaboration with her husband John Cassavetes where she shines in a critical supporting role meanwhile THE NEON BIBLE is a rare lead offer she accepts after Cassavetes’s passing in 1989, and a Terence Davies’s picture is hardly something one shall quibble about.

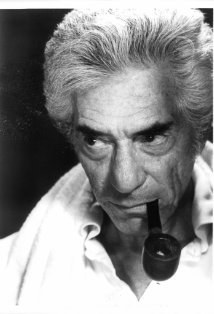

A CHILD IS WAITING is atypical among Cassavetes’ oeuvre, a studio assignment he accepts and then regrets by vehemently disavowing it after the magisterial interference of producer Stanley Kramer in the cutting room (the same old story of the battle over ownership between the bankroller and the artistic architect). Headlined by Lancaster and Garland (for the latter, it is her penultimate motion picture), the film is an addition to the so-called “heuristic drama” that Hollywood often receives a self-congratulatory pat on its own back for being socially responsible for exploring those lives on the margin. It tackles the taboo issue of treating intellectually disabled and emotionally disturbed children, whose rawness and zest are boisterously captured in Cassevetes’s characteristically intimate close-ups.

Thematically, the film flaccidly pits Dr. Matthew Clark (Lancaster), the head of the Crawthorne State Mental Hospital, against Jean Hansen (Garland), his new employee, on their different methods: discipline versus love (especially maternal love). Which is the better remedy? Apparently, the answer should be neither. Any child needs both to grow up healthily, why the institution cannot offer both? That is the question dodged by the film. Additionally, A CHILD IS WAITING touches on the touchy topic of monetary expense. Mentally disabled children or physically disabled ones, who are worthier of government funds? Again, why this has to be a choice anyway?

It is overt that Jean is driven by a savior complex as she draws (almost exclusively) closer to Reuben Widdicombe (Ritchey, holding his own against an august Lancaster with silent recalcitrance), a boy of an intelligence of a 5-year-old and afflicted with a speech impairment. Against Dr. Clark’s interdiction, Jean seeks out Reuben’s mother Sophie (Rowlands), who, in spite of her unmitigated affection, agrees that for Reuben’s own sake, she is better severing the tie with him. Jean’s do-goodism doesn’t do any good to Reuben and only makes the matter worse. So she is put through Dr. Clark’s mansplaining that those special children do not need to be saved. On the contrary, it is Jean, a middle-aged spinster trying to find a purpose in life, needs them. A viewer can totally comprehend the disconcerting overtones here.

A Thanksgiving pageant is arranged in the film’s climax, and it is very moving to see Garland sing again on the screen, even for a rather short part, who strains to contain the emotion that swells up in her. Jean Hansen isn’t a particularly interesting role a priori, but an out-of-sort Garland ekes out a strenuous presence that often invites audience to ask what has happened to Ms. Hansen. While Lancaster is excellent in both tender and authoritative registers, supporting players like Steven Hill manages to do a serviceable job as Reuben’s father and Paul Stewart occasions great equilibrium as Goodman, Dr. Clark’s associates, it is Rowlands who outshines everyone else. Impeccably photogenic in her youth, Rowlands exquisitely and potently justifies Sophie’s choice with just enough pathos and certitude.

32 years later, a sexagenarian Rowlands plays Aunt Mae in THE NEON BIBLE, an over-the-hill lounge singer who picks up her marbles and go stay with the nuclear family of her sister Sarah (Scarwid), and becomes a beacon of joy, spirit and inspiration for her nephew David (Tierney and Bell, playing him in different ages, both are wonderful findings) in a 1940s Southern town, Georgia, USA.

Davies’s poetic and scenographic aesthetics (the reverent sense of gravitas stemming from those vertically and horizontally panning shots, the majestic matte background of a theater play), matched by some cracking legerdemain of flowing superimpositions and invisible editing choices (splicing together scenes between reality and imagination, scenes undergoing a temporal hiatus), and poems of course, all conspires to a languid pace that is devoid of any kinetic exigency, a trademark Davies’s pace.

David, a meek boy doesn’t fit in with other boys, is a nonconformist like his aunt, who is unmarried and isn’t shy away from serial monogamy although she is not longer a spring chick. Together, they share a kindred spirit that bothers David’s father Frank (Leary), a violent, headstrong rube could’ve been a terror if ever he would return from the ongoing WWII (I’m happy to report that doesn’t happen). Neither the film dwells in the more predictable area of Bible-thumping mania, where materialistic gain is masked as fervent evangelism to brainwash countrified folks (a cameo by Leo Burmester as a frenetic preacher is more than enough). If anything, Davies’s outsider stance grants him a more leveled-headed perspective of American follies limned so vividly in John Kennedy Toole’s source novel. So he is able to resist from making a meal of them, instead, he sails through the hoopla with a quietening visual metaphor of entering a void as the camera zooms in and gazes statically.

After a botched puppy love (exchanging for two fierce blood-inducing slaps), an inimical invite by a lonesome woman (Conroy, representing menace in the most feminine form) he intuitively declines, eventually, David’s coming-of-age baptism ends with a harsh note, left alone with two deaths (one of which he becomes the enabler) and he winds up as a fugitive on a hurtling train, heading to nowhere. A 16-year-old boy like him starts his life anew all by himself? Apparently the downbeat prospect of his future doesn’t land with most audience, as the film fails to make a splash upon its release, even among Davies’s works, often pegged as a minor achievement.

But two performances are outstanding. Aunt Mae is a woman of steely resolve and sharp discernment, and Rowlands makes every second of her appearance worthwhile because there is no pretense here. She has fought and failed, lived and loved, yet, no sentimentalities can drag her from pursuing her fortune when most people like her are more than happy to resign to the fact that their ships will never come in. She also encourages David to accept his alterity, no matter how hard it will be, it is the only way to get through the growing pains of adolescence. But she is not a savior, she just embraces her own mess and makes it at least tolerable. Speaking of inspos of unconventional woman, Rowlands’s Aunt Mae is here to stay.

Another undervalued performer is Scarwid, whose Sarah is a heart-rending specimen of a small-town American wife, a beaten angel of the house whose entire universe revolves around her husband. So when her husband pops his clogs, he also takes her away with him, leaving an empty husk behind compounded with all the damage he has done. Sarah is a tragic outgrowth of a sexist, patriarchal society and via Scarwid’s tremendously emphatic force and expressions, THE NEON BIBLE hits its highest note poignantly and resoundingly. So now it is a high time to dust it off from obscurity and reappraise it in memory of both Davies and Rowlands.

referential entries: Cassavetes’s FACES (1968, 8.0/10), HUSBANDS (1970, 6.8/10); Stanley Kramer’s JUDGEMENT AT NUREMBURG (1961, 8.1/10); Davies’s THE LONG DAY CLOSES (1992, 7.6/10), THE HOUSE OF MIRTH (2000, 7.7/10).