金发女郎的爱情 Lásky jedné plavovlásky(1965)

又名: 金发女郎之恋 / A Blonde in Love / Loves of a Blonde

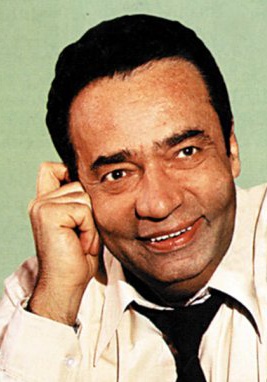

导演: 米洛斯·福尔曼

编剧: 米洛斯·福尔曼 雅罗斯拉夫·帕布塞科

主演: 哈娜·布赖霍娃 乌拉迪米尔·布戳特 弗拉迪米尔·门西克 伊凡·帕瑟 Jirí Hrubý

制片国家/地区: 捷克斯洛伐克

上映日期: 1965-11-12

片长: Argentina: 90 分钟 IMDb: tt0059415 豆瓣评分:7.5 下载地址:迅雷下载

简介:

- 金发少女安杜拉(Hana Brejchová 饰)是一个在捷克某小镇制鞋厂工作的女孩,青春年少的她和同龄人一样渴望一段浪漫完美的爱情,但在这个男女比例严重失调的小镇上,她的愿望似乎有些渺茫。镇上的青年汤达(Antonín Blazejovský 饰)展开爱情攻势,然而始终无法获得安杜拉的芳心。某天,偶然流浪于此的青年钢琴家米达(Vladimír Pucholt 饰)适时打开了安杜拉的心扉,她和这个来自布拉格乐团的文艺青年度过浪漫激情的一夜。从此以后,安杜拉对米达念念不忘,更决定启程前往布拉格寻找爱人。她要的是真挚的爱情,而米达却只当那是一夜的露水姻缘……

演员:

影评:

- 一部黑白片,摄于1965年。

我还是挺关注一些技术上的细节,比如影片的镜头调用问题。关于Milos Forman,在这里我能说些什么?或许什么资格都没有,只因为------我只看过他的一部影片。

很多影片都存在这样那样的问题,做得再好也达不到十全十美的程度。但这样的一部黑白片,拍于1965年的,似乎已离这个结果很近了。

在镜头调用,场景过渡上,完全能看的出导演的功力来(当然这其中也有摄影,剪辑师功劳)。看一两段,基本上就能知道“此导”为何等人物。当中也有大智若愚的,这只在极少数。对于一个内容苍白的故事来说,如果在述事方式上再没有任何创新,那简直就是在谋杀胶片。虽然没人喜欢干这个勾当,但天资差的还是免不了要走这条路。

这是个非常流畅的故事,如果用设计中的术语来形容,那就是“文字块色彩”呈现灰色,均匀的灰色。这已经是非常高的境界了。

因此,我推荐这样一部影片,在这里。希望大家能看看。

看了这部影片,你或许会发现一些JIM JARMUSCH的黑色幽默来。但我想这当中没有谁摹仿谁的问题,毕竟都是名导,在“借鉴”的底线上会控制得很好。你也可以把它当作一部青春片来看,但至少有两点是不同的,一是黑色,二是幽默。

还是来谈谈它的镜头调用。

让我们来注意一下它的开头,也就是舞会的那段。你能看到镜头是沿着某一特定轨迹运行的:或是被推动的餐车,或是一个人目光的转移,抑或是行走中的特定人物。当镜头从一个地点转移到了另一个地点,你能感受到一种从容的过渡,就像写散文,尽管可以写的东歪西岔,但你能找出一条主线来。这条主线就是促使镜头运行下去的自然动力。也就是我现在正在看那里,镜头就转到那里;我注视的地方有人走过来,镜头就移到来人身上;然后这个人走向厨房,镜头就跟随着他;知道他半路上又和旁人说了句什么话,镜头再移到旁人身上。最后这人和我递了个眼色,镜头又重新移回到我身上。这样,一个轮回就转好了。我们可以在大脑中运转一下,将这个过程运转一下。将之添油加醋,并且在景深,角度,运行速度上加以控制和发挥,你就能感受出导演的视角来。

事实上有这么简单吗?当然没有,这大部分是剪辑的功劳,后期剪辑。但景深和角度等控制问题却得看摄影的了。然而这些又都是导演的基本功。如果连这些都掌握不好,那就只能去拍拍电视片了。

电影有各种各样的拍法,所谓的成功没一个固定的标准,要讨所有人的喜欢是不现实的。不过我还是挺喜欢那些手法新颖的影片,而不管内容会有多苍白,至少对电影本体的发展还是做出了贡献的。

这部《金发女郎之恋》是少数几部让我惊叹的电影。它所显现出的功力使我认识到电影----这种艺术形式也能在叙事和演绎上摸高到一般文学作品达不到的意境。它让太多21世纪使用彩色胶片的电影人自叹弗如。希望这是我说错了。 ##21637 #PCC 捷克新浪潮标志性作品,以闺房密语展开的非线性叙事效果非常好,似乎要上演一部完美的爱情故事,年轻一代视角的发反叛与自由,现实主义描绘出的日常也极度真实且带有复杂性,电影的批判和讽刺呈现的也非常到位,尤其是对于男性角色的塑造和女性角色情感的细腻呈现的对比,幽默中又带着一种淡淡的悲伤很能引起我的共鸣,最后的回收也不失为一种极致的讽刺。这些似乎都是捷克新浪潮风格的特点,电影的故事非常简单,但是以女主的视角讲述结视听的呈现效果非常好。

视觉上,构图还是蛮独特的,几次边缘化角色的效果反而非常好,光影上的呈现也非常棒,表达力和视觉冲击力很足。非常喜欢手部特写的运用,感觉非常能让人带入那情感中。

听觉上,除了中段舞会的歌曲实在有些长其他的都非常满意,尤其是温情部分的呈现。收音效果也非常好。

电影改编自一本Papousek未出版的书,书中描绘了作者在1945年的还是青年时的见闻,导演提及他不喜欢空洞与虚假,他只想呈现真实,提及意大利新现实主义的现实主义和法国新浪潮的写实风格启发了他的创作,还着重强调了两部意大利新现实主义作品影响了他,分别是《风烛泪》和《艰辛的米》(这两部我还都是最近在BFI意大利新现实主义回顾展看的)。

《金发女郎之恋》(1965年)是米洛斯·福尔曼继《黑彼得》之后拍摄的又一部力作。在捷克兹鲁克一家皮鞋厂打工的金发女孩安卓拉,跟女友玛丽讲述了她跟布拉格钢琴手米达的交往史。安卓拉之前有一个男友冬达,但小气的冬达让她很不爽,之后就分手了。

在一次军民联欢舞会上,三名有妻室的军人,相中了安卓拉、玛丽和让娜这三个一桌的女孩,请她们喝啤酒,邀她们跳舞,继而他们想入非非要邀她们一起去森林玩,还是被犹豫不决的女孩拒绝了。正好,舞厅钢琴演奏手米达目睹了这一幕,遂找机会跟安卓拉攀谈起来,没想到,经不住他的热情相邀,二人就同居了一夜。而三名军人为了这三个女孩吵嚷不断,最后只有一名军人跟另一名女子得以同宿。

让人讶异的是,当时的捷克社会体制,导演拍的这样大胆,实在令人感佩,也难怪1968年“布拉格之春”后导演就逃往美国了。当然,相对于我们所熟知的社会主义国家,当年的东欧还算平和,至少酒吧、古典及流行音乐和正常的爱情,还没被视为资产阶级大毒草,没有如我国走到“文革”这样的极端。单看本片那浩大舞会的场景就叫人瞠目结舌。

这场舞会的细节极为逗乐,先是三名军人让服务员送酒给对面安卓拉她们,他却送到了隔邻的一桌,惹得他们无地自容,都缩着脖子,结果他们让服务生改送,等服务生再端起酒送到安卓拉她们,就轮到这桌女子难堪了。

有趣的是,这时,其中一名军人因为要跟女孩跳舞,怕女孩知道他已婚,就摘下戒指,结果戒指偏滑到那桌正不高兴的女人脚下,他只得狼狈地爬在桌底下扒开她们的脚拿戒指。想必军营枯燥的生活,让他们一旦出来看到女人,也就如狼似虎地无所顾忌了。

另外一个场景是,工厂女辅导员召集女工开会,她说道“年轻姑娘的贞操不是陈词滥调,失去了它,他们就不会在乎你们……和一个谦逊的人交往,他会爱你一生,这是值得的。”其实,在女工云集的工厂这种教育还是必要的,至少让她们有了一个心理认知,这并非生硬地说教。这同时也说明当时捷克的整体社会环境还算开明和通达。

那夜安卓拉甜蜜的跟冬达相拥着。她问冬达有没有女友。他先是支吾,后追问下,他连嚷道“我在布拉格没女朋友”。这让她吃了定心丸似的。她说“我自杀过,父母总是吵架,后来离婚了,你看,我这里有个小伤疤”。她给他看割过手脉的手腕。冬达说我的父母也离婚了。可谓惺惺惜惺惺。安卓拉是个温柔又渴望稳固爱情的女孩。

自与冬达那夜后,她就一直怀着这美好的期许,所以,她拎着皮箱就坐着车来到布拉格,找到了冬达的家。冬达的父母并没有离婚,他们为了安卓拉的到来争执了一夜。父亲希望留她住一夜,她没地方去。母亲则说不应收留她,也不知她来干什么。二人一直絮叨着,直讲得安卓拉打了嗑睡,她就睡在客厅的小床上。夫妻俩在卧室又吵嚷着。母亲说难道她不知道他早订婚了吗。父亲说这小子到处拈花惹草,得让他早点结婚。

半夜,冬达回家了,给吓了一跳。一家三口挤在一床,为了安卓拉吵个不停,这让客厅里蜷缩一团的安卓拉伤心不已。她被骗了。这儿只是她的又一个伤心地而已。此时,动听的音乐《索尔维格之歌》“啊……”的响起,悠悠中,让人有断肠人在天涯之感。

镜头再回到现实中的安卓拉对玛丽平静地讲述着。伤怀的安卓拉明知这段爱情无望却仍满怀期待,如同歌中唱的“冬天不久留,春天要离开,夏天花会枯,冬天叶要衰。任时间无情,我相信你会来,我始终不渝朝朝暮暮,忠诚地等待。啊……啊……啊……”

2013、12、13

选自海天出版社出版的影评集《看不见的电影》

- Loves of a Blonde

By Dave Kehr

When Milos Forman’s Loves of a Blonde had its American premiere at the New York Film Festival in 1966, it was an immediate sensation. Nothing quite as fresh and apparently spontaneous had appeared on the scene since François Truffaut’s The 400 Blows seven years earlier. Bosley Crowther, the chronically stuffy chief critic of The New York Times, flew into uncharacteristic paroxysms of pleasure, describing it as “delightfully simple and sure. It is hopeful—but realistic. And full of delicious characters.”

Usually, when a film achieves instant acceptance, that means there is something wrong with it—that it is too obvious, too sentimental, or too eager to please. None of this is true of Loves of a Blonde, which remains an amazing balancing act of subtle social satire and adolescent romantic longing, of blank despair and irrepressible hope. After repeated viewings, the film begins to betray its somber, dark side, the sense of entrapment and injustice that lies behind its images of young love. And yet repeated viewings do not diminish the charm, sincerity, and gentleness of Milos Forman’s vision; this is certainly one of the most sweetly seductive films ever made, an ironic quality in a film whose main theme is the cruelty of seduction and its costly aftermath.

The film takes place in the provincial Czech town of Zruc, which Forman sketches in with a handful of quick shots: a train station, a housing block, a shoe factory—the latter staffed by dozens of young women, who have been forced to relocate to this gray, remote area by the Communist government. If workers are needed to make a state-imposed quota in the Communist planned economy, workers will be provided, with their consent or without.

Forman does not make a heavy, didactic point of this loss of personal freedom, but the sense of social imprisonment, of individuals sacrificed to the needs of an invisible, unapproachable government, informs every scene of Loves of a Blonde. The film opens with the benign manager of the factory asking army officials to place a regiment in Zruc, as a way of redressing the local imbalance of available males and yearning females. “They need what we needed when we were young,” the manager says to a sympathetic army officer, subliminally evoking the days before World War II and the Communist takeover. If there is one answer to totalitarianism, it is sexuality, an inexhaustible source of pure, anarchic energy.

Loves of a Blonde breaks down into three acts, each of which could stand alone as a short story. Each segment takes place in approximate real time, and each is confined largely to a single setting. In the first section, one of the factory workers, Andula, a young blonde with a wide, sensual mouth and dark, anxious eyes, is induced by two giggly friends to attend the first mixer between the women of the factory and the men of the base. Instead of handsome young soldiers, the girls are disappointed to find a room full of pudgy, middle-aged men, reservists doing their annual duty. In the second, Andula succumbs to the charms of Milda, a young pianist from Prague who has been playing at the dance, and returns with him to his hotel room. The final section finds Andula, some time later, leaving for the capital in search of her lover; she finds the apartment of his squabbling parents, who let her in to await Milda’s return.

Over the course of the three acts, the film’s context evolves from social satire (set in a public space) to emotional intimacy (confined to the private space of a single room and a single bed) to domestic drama (set in the awkward private-public space of a family apartment). The thematic shifts reflect the shifts in setting: the first section is centered on youth and infinite possibility; the second on young adulthood and romantic fulfillment; the third on maturity and inevitable disappointment. For Forman, Milda’s parents—a pushy, overprotective mother and an indifferent father, collapsed in front of the television—represent the young lovers projected into the future, as the romantic idealism of youth gives way to the glum pragmatism of middle age.

Though Forman has fun with his characters’ weaknesses and moral blind spots, he never ridicules or condescends to them. The camera, manned by the gifted Miroslav Ondricek, seems to caress the young lovers, holding them together in snug, intimate frames, focusing on Andula’s pale skin and sad eyes. The film’s low-contrast lighting infuses all of the locations, as inherently grim as they may be, with a sweetly mysterious softness, as if a principle of compassion existed in the world alongside its cruelty.

Loves of a Blonde dances along the thin line between dreams and disillusionment, as sympathetic to its heroine’s aspirations as it is certain that they can never be fully achieved. As Forman’s own work has matured, he has continued to explore this conflict—in the struggle between the young Mozart and the aging Salieri in Amadeus, for example, or between the predatory sexual adventurers of Valmont and their virginal victims. The loves of this blonde are the loves of us all, as essential as they are impossible.

原址: