有序或无序 به ترتیب یا بدون ترتیب؟(1981)

又名: Orderly or Unorderly / Orderly or Disorderly

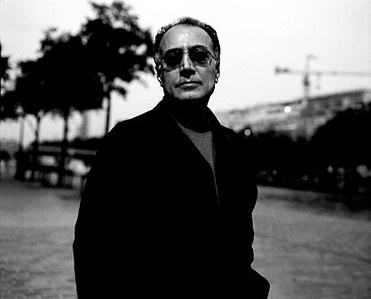

导演: Abbas Kiarostami

编剧: 阿巴斯·基亚罗斯塔米

类型: 短片

制片国家/地区: 伊朗

上映日期: 1981(伊朗) 1995-10-14(日本)

片长: 17分钟 IMDb: tt0082050 豆瓣评分:7.4 下载地址:迅雷下载

简介:

- 秩序是维护良好社会组织的纽带,为了表明这个公认的原则,阿巴斯拍摄了一系列短片。一个同样的行为先是以和谐的和有组织的方式开始,然后再以无政府主义的和突然的方式展开,阿巴斯通过一些例子(比如交通规则)以对比的方式说明了秩序的重要性。

演员:

影评:

阿巴斯短片集

《颜色》《课间休息》《有序与无序》《面包与小巷》《一个问题,两个方法》

伊朗导演我看的不多,只记住了他们一个突出的特点“隐藏摄影机”。但没想到,他们还能在破败的现实里面找出温暖明亮。阿巴斯的这四个短片被定义为儿童教育片,只是因为讲述的主体都是孩子,它们面向的始终是成年人。所以我庸俗地,从一个非儿童的角度看待这些柔软的心灵。

(私人排序:面包与小巷、颜色、有序和无序、课间休息、一个问题两种方法)

面包与小巷更像是一个寓言,故事很简单,一个小孩遇见一条大狗朝他叫,害怕地停住脚步,几次张望后跟着一个老人身后过去。谁知老人转个弯就到家了,他也被大狗追逐。慌乱间他扔给大狗一块面包,大狗因此安顺地跟在他身后,直到小孩回到家,他的妈妈一把关上门。而大狗趴在门外,向另一个过路的孩子叫了起来。

就像菊次郎的夏天一样,直到结尾才能意识到主角其实是那只凶恶的大狗。大狗始终在这样的一个循环里,小孩是我们关注的主体,却仿佛错位一样处于误入的状态。导演设置的目光重点的转移,让故事更加的妙趣横生,成人童话的色彩和可观性更加明显。

除了现实意义之外,《面包与小巷》的隐喻意义也极为丰富。悠长的小巷,循环往复的人生;面包,以食物作为友好的象征;凶恶的“恐惧”,转化为守护;守护者则客串了维护者、封闭者。事实上,作为一个儿童寓言故事,《面包与小巷》的隐喻意义是极为内敛的,我们可以通过普通观看获得第一层故事内涵,而在结尾感受到第二层意义内涵,再在回顾品味时,思考第三层哲学内核。

这是一种驾轻就熟的构建方式,叠加三层意义,宛如一个苹果一样,把核包裹起来,而苹果核,也就成为下一颗苹果的种子。

《颜色》的实验性太强,仿佛是一本儿童读物,以长者、父母的角度解说他们对于颜色认知的初印象。视角的成人化干预表达,使得政治含义和教化含义突出起来,尤其是在结尾黑色终结色的解说。

因为阿巴斯回顾展,有机会在大光明影院看了他的短片合集,气氛热烈,观感奇妙,观影时暗暗感慨:原来阿巴斯曾经是这样的,果然还是阿巴斯,怪不得后来他拍出了…

看完乡村三部曲再回顾短片集,回溯似曾相识的阿巴斯,比如《面包与小巷》中吊人胃口的紧张与不安;《课间休息》中的男孩盯着足球时,世界只剩下足球的声音;《我也能》中耐人寻味的结尾;《如何利用闲暇时间:给门板刷油漆》中鲜亮而治愈的色彩;《一个问题的两种解决方法》中的逗趣摆拍和对比反复;《颜色》中突然跳脱破坏起来,用枪砰砰射击彩色玻璃瓶;《牙疼》中机智而残酷地在孩子的哭声中一本正经地解释为什么要刷牙和怎样刷牙;《第一解决方案》中音乐和影像画面的统一节奏;《教师赞歌》中的大量采访,离题感叹下,80年代伊朗人的着装让人穿越到了意大利电影;个人最喜欢的一部《有序或无序》,阿巴斯评论音轨的介入,暴露在拍电影的事实,以及在无序的现实里捕捉到有序的场景是多么困难,引人深思的幽默,再次离题感慨下,80年代伊朗街头的汽车色彩真丰富,无序的混乱里有种奇异的活力;《合唱团》中用助听器表现不同的声音,孤独和边缘的老人,老少相互关怀,带着希望的温暖结尾都能让人联系到他之后的作品。

回顾展之前的分享讲座上,btr老师推荐了Jonathan Rosenbaum的影评,于是找来细读。本文节选搬运自影评人Jonathan Rosenbaum的Before He Was Famous (Kiarostami’s Early Shorts)。Jonathan在此文中系统地梳理了阿巴斯早期兼具实验性和趣味性的短片作品,并将其与之后更为成熟的代表作品中展现的阿巴斯式重复和对比联系了起来。

Before He Was Famous (Kiarostami’s Early Shorts)

From The Guardian (21 September 2002). I continue to find it frustrating that almost sixteen years later, what I regard as Kiarostami’s two best shorts, Two Solutions for One Problem (1975) and Orderly or Disorderly(1981), still aren’t available on any DVD or Blu-Ray (although Scott Perna has just emailed to remind me that the former can at least be accessed on YouTube). The principal reason was that Kiarostami himself didn’t like them. He once told me that even the second of these was made before he regarded himself as a film artist — something I continue to find baffling, and astonishing. But now that Criterion has announced that it will be restoring and releasing all his films, this lack of availability will apparently change. — J.R.

The eight short films made by Abbas Kiarostami between 1970 and 1982 offer an interesting riposte to critics who claimed during those years that they knew what was going on in world cinema. Even in Iran, where the shorts were made, none constituted much of an event. And considering how deceptively modest they are, they probably never would have attracted much notice anywhere if their director hadn’t gone on to make a string of masterful features over the past 15 years (the most recent of which, Ten, is about to open here). Yet there’s nothing else in cinema quite like them.

All this only confirms that it’s preposterous to pretend that anyone can know the state of world cinema — unless, that is, we reduce “world cinema” to the films that get promoted, most of them idiotic. For too long, we have been letting our cultural commissars — producers, exhibitors, distributors, official and unofficial publicists (including critics) — dictate the limited range of choices we’re supposed to want.

Kiarostami’s simple yet profound early shorts (all but one of which are at the National Film Theatre in London next week) are a good example of the kind of cinema that typically falls between the cracks. They were all produced by a state organisation called Kanun, better known as the Centre for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults, founded by the shah’s wife. Their director had been a commercial artist throughout the 1960s, starting out with posters and book jackets before graduating to TV commercials and designing films’ credit sequences. He was pushing 30 when the owner of an advertising agency that he had worked for, now the director of Kanun, invited him to help set up the organisation’s film unit in 1969.

Assigned to make educational films, Kiarostami wound up creating a particular kind of pedagogical cinema that was both experimental and playful, though he once said that he didn’t regard himself as a film artist when he made them. They played a substantial role in making films about children fashionable in Iran, though they weren’t always made for children. In fact, the last two films that he made for Kanun went out into the world in the early 1990s as grown-up art features, Close-up and And Life Goes On… The first of these, Kiarostami’s initial calling card in the west, contains no children at all.

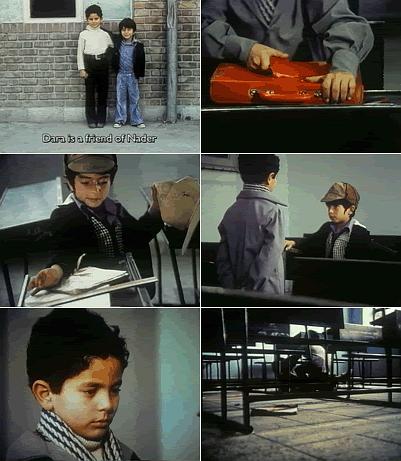

A few of the shorts — Breaktime (also known as Recess, 1972), Two Solutions for One Problem and So Can I (both 1975), Orderly or Disorderly (1981) — are set wholly or partially inside schools, and nearly all qualify in some fashion as didactic works, comparable to what Bertolt Brecht called Lehrstücken, or learning plays. The only film missing from the NFT program — the least interesting and incidentally the most didactic — is the 1980 Toothache, explaining how and why kids should brush their teeth.

Working within such a framework, Kiarostami could reflect on the advantages of cooperation over conflict (in Two Solutions for One Problem), draw on animation (used briefly in So Can I) or abstraction (as in The Colours, 1976), comically raise philosophical questions about order and disorder (Orderly or Disorderly) or formal as well as social questions about sound (in The Chorus, 1982), and even explore how a man might roll a tyre down a highway (Solution, 1978) or a little boy with a loaf of bread get past an unfriendly dog.

The latter is the subject of Kiarostami’s first film, Bread and Alley(1970), drawn from an experience recounted by his brother Taghi (who was credited with the script), and choreographed to a jazz version of the Beatles’ Ob-la-di, Ob-la-da. His second film, Breaktime, follows a boy heading home from school after being ejected from class for breaking a window, and Kiarostami’s design background becomes apparent when an early intertitle appears neatly and eccentrically over a wall at the end of a school corridor.

Try to imagine Laurel and Hardy directed by Robert Bresson and you may get some notion of the hilarious performance style of Two Solutions for One Problem, a syncopated, deadpan grudge match between two schoolboys that ensues after one returns a borrowed book to the other with its cover torn. The camera lingers on the resulting damage, including a broken pencil, a ripped shirt and a split ruler, while an offscreen narrator explains whose possessions got destroyed; then the story begins again with the torn book cover being glued back by the guilty party, proposing a second solution to the problem.

Children imitate the movements of other creatures in matching shots in So Can I; contrasting forms of behaviour as seen at a school and a busy traffic intersection are the subject of Orderly or Disorderly. Other kinds of repetitions, parallels and contrasts recur in these shorts as formal principles as well as subjects. In Kiarostami’s subsequent features, where they’re no less central, they often wind up structuring the action.

In Where Is My Friend’s House? (1987), this entails running up and down a zigzagging hillside path; in the documentary Homework (1990) and the fiction film And Life Goes On… (1992) it consists partly of asking several people the same questions. In Through the Olive Trees (1994) it involves two amateur actors in a film comically blowing take after take.

Taste of Cherry (1997) follows a middle-aged man in a car repeatedly asking strangers to bury him if he succeeds in killing himself; The Wind Will Carry Us (1999) shows a brash media person in a remote Kurdish village repeatedly driving up a hill to receive calls on his mobile phone.

This form of patterning is often a way of posing questions, and I would argue that Kiarostami belongs to that tribe of film-makers for whom a shot is often closer to being a question than to providing an answer. The tribe includes John Cassavetes, Chris Marker, Otto Preminger, Jacques Rivette, Andrei Tarkovsky and Jacques Tati (in his last three features). All these film-makers confound many spectators by not providing the sort of narrative assurances they expect from cinema, and most of them have a particular predilection for what might be termed philosophical long shots and all the questions these imply.

The Colours recalls the abstract montages of Hollis Frampton’s Zorn’s Lemma in terms of its colour coding, but it also indulges violent fantasies involving cars, guns, little boys and paint. The Chorus, by contrast, explores sound and its absence in narrative terms, through the story of an old man who escapes urban noise and his granddaughter by turning off his hearing aid.

The most remarkable of the shorts, Orderly or Disorderly, shows boys leaving a classroom, heading for a water fountain and getting on a bus, then offers a cosmic overview of adults driving through a busy section of Tehran. Each action is shown twice, with the boys or adults behaving in an orderly or disorderly fashion, though the degree to which this is being staged or documented is teasingly imprecise — a kind of ambiguity that continues in Kiarostami’s work all the way up to Ten.

The difference is that whereas in the 1982 short Kiarostami was playfully foregrounding his work as a director, including his own instructions and comments to his crew in every take, in Ten, two decades later, he’s avowedly trying to make a film without any direction at all, comparing his own function to that of a football coach, and ringing a bell between sequences as if they were separate innings. In this new film, one might alternatively say he’s proceeding more like a journalist than like a teacher. But as Close-up demonstrated, few modern directors handle journalism so artfully and so ambiguously.

...

全文链接:

阿巴斯影展前的讲座上,btr说到阿巴斯的简单平实具有欺骗性,观众可以从不同的层面去喜欢他,越看越喜欢,越看越理解彼此之间的关联。阿巴斯的重复也蕴含着丰富,他利用重复创造了一种句法。个人对阿巴斯式重复的理解像是音乐里的模进。btr以《生生长流》为例,导演将车窗摇下来问路,有时候得到的回答是关于人生方向,有时是阶级差异,有时是确实需要高德地图。

个人来说,观影无止境,顶礼膜拜的大师不多也不少,想要借彼之慧眼来看世界的大师屈指可数,除了安德烈·塔可夫斯基,阿彼察邦,就是阿巴斯。话说怎么这么巧都是A字辈的?!

戈达尔对阿巴斯的评价近乎震天动地:电影始于格里菲斯,终于阿巴斯。对于这句评价,阿巴斯曾回应说:戈达尔现在已经不这么想了,电影不会在我这里终结,但我会让电影稍稍改变一点方向。而戈达尔又颇为婉约而机智地回应说自己不是不再喜欢,而是最近几年没再看阿巴斯的作品…

电影止于阿巴斯,是至高的赞许,细想也令人难过。