重婚泪 The Bigamist(1953)

简介:

- 哈里(艾德蒙·奥布莱恩 Edmond O'Brien 饰)和伊娃(琼·芳登 Joan Fontaine 饰)是一对非常恩爱的夫妻,两人唯一的遗憾就是无法拥有一个属于他们的孩子,为了弥补这个遗憾,夫妻两决定领养一个孩子。

演员:

影评:

Kino Lorber于2019年发行的Lupino蓝光套装,4k修复,7.8~7.9分 1,"On that bus this afternoon, I felt just as lonely as you did. "——这是片中我印象最深的一句台词

2,我个人称之为男性视角的《相见恨晚》;Double life,并以第一人称男主叙事的方式,让人很容易联想起怀尔德的《双重赔偿》

导演对重婚这一现象并未投射更多道义上的指责,反而在探寻思考造成这一结果的社会性根源,也给予了男女两性在婚姻关系上,有时不可避免结局的同情。如果要指摘人物塑造上的缺陷,那就是琼·芳登的妻子形象太过天真与完美了

3,不知是否原始素材损毁太严重了,4k修复之后依然看到不少噪点

4,彩蛋:担任本片剧本和制片的是Lupino的前夫Collier Young(两人于1951年离婚),可造化弄人的是,1952年Young再婚时娶的不是别人正是Fontaine!不知是否这样的经历促成Young写下了电影的本子,看着荧幕上Lupino和Fontaine的角色共同追随一位丈夫,想到现实中的她们也曾拥有同一位男人,真是不得不套用那句老话:人生如戏

当最后法庭上Lupino与Fontaine表演对视的时候,她们想的又是什么呢,哈哈

本片我们看完了之后如果用现在的意识形态去框化它,就是严重错误的。艾达卢皮诺作为一个进步女性她有局限性?即使自己当了导演也无法在男权社会里面完全发声?不如某某某电影,一个双女主设置的电影为什么不手撕渣男(这个重婚者),设置连最后的法庭戏似乎都对该重婚者表现了怜悯?

自己的辩护律师都对自己的当事人表示当事人必须彻底毁灭

自己的辩护律师都对自己的当事人表示当事人必须彻底毁灭 这真的是法外容情?

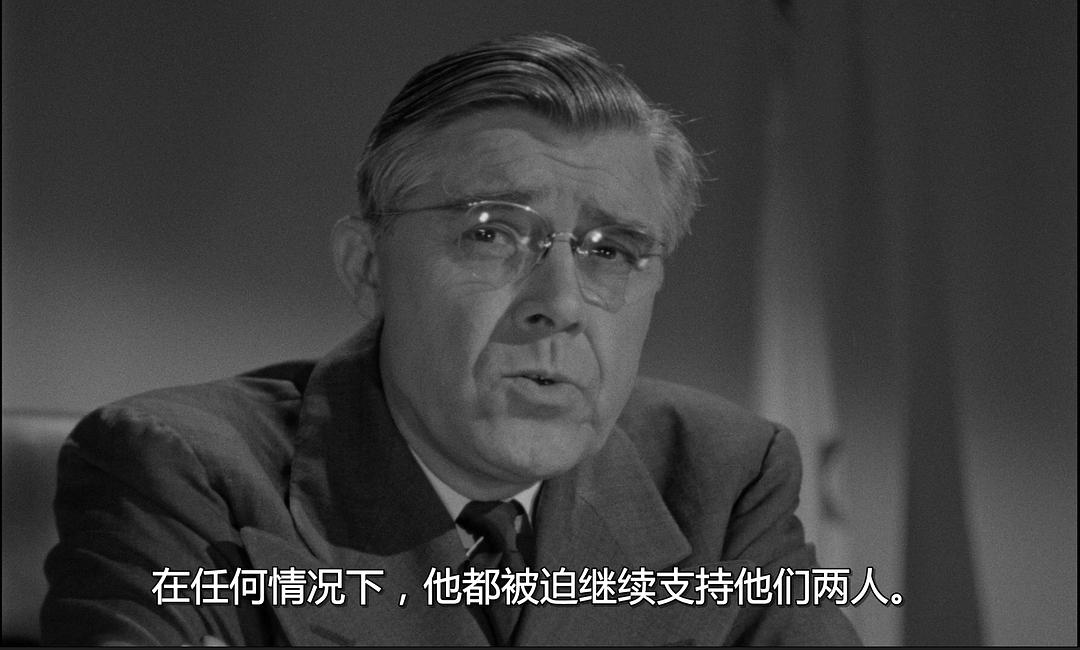

这真的是法外容情? 法官的综合陈词,重婚绝对是不对的,是不道德的

法官的综合陈词,重婚绝对是不对的,是不道德的 男主要求法官重判他,以缓解内心的罪恶感

男主要求法官重判他,以缓解内心的罪恶感没等男主说话这句话,马上快切两位女主,这并不是偶然的

琼芳登饰演的事业型女性帮男主的事业蒸蒸日上,含情脉脉的看着他

琼芳登饰演的事业型女性帮男主的事业蒸蒸日上,含情脉脉的看着他 艾达卢皮诺饰演的女服务员虽然过得十分拮据,但人狠话不多(对应男主的是talk about这个词)她根本无论金钱和感情都不想依附于男性

艾达卢皮诺饰演的女服务员虽然过得十分拮据,但人狠话不多(对应男主的是talk about这个词)她根本无论金钱和感情都不想依附于男性这真的是艾达卢皮诺在当导演后也无法逃脱的局限性?

镜头不断的在法官和两位女主和男主之间转换,男主其实只是两位女主的提线木偶而已,他还必须在获得自由后经济支持两位女性

镜头不断的在法官和两位女主和男主之间转换,男主其实只是两位女主的提线木偶而已,他还必须在获得自由后经济支持两位女性 由法官讲出了本片最关键的一句话。

由法官讲出了本片最关键的一句话。 艾达卢皮诺走得出这个门,而男主内心上是走不出去的

艾达卢皮诺走得出这个门,而男主内心上是走不出去的 琼芳登也走得出这个门,男主是走不出来的,内心的煎熬

琼芳登也走得出这个门,男主是走不出来的,内心的煎熬我现在公布本片的形式影思:任何人都需要对自己做的事负责,不管他受到了多大的外界的干扰。

为何形式影思不是:重婚者是不对的,女性是懦弱的?那么我用开场戏来证实这点。

儿童收养中心的主任(他是本片主要的线索人物,实际上他也是男主的对照组,他是正面的,但是他也犯过错)在送走男主和琼芳登出门之后,给的镜头的本中心的女服务员(清洁员)

这个做清洁的老太太镜头是否多余,人物是否多余?

这个做清洁的老太太镜头是否多余,人物是否多余? 在主任准备对上级进行汇报录音的时候,这名老太太不合时宜的进来了

在主任准备对上级进行汇报录音的时候,这名老太太不合时宜的进来了 主任一起在前景做刚才的领养夫妇的介绍,而后景的老太太一直在做清洁,弄出无数的吵杂声

主任一起在前景做刚才的领养夫妇的介绍,而后景的老太太一直在做清洁,弄出无数的吵杂声 甚至走道中景来造成了她才是主导的站位,不停的收拾

甚至走道中景来造成了她才是主导的站位,不停的收拾这艾达卢皮诺怎么瞎导演啊,造成这么大的失误,弄这么一个老太太干吗啊?

不仅观众被这个搅局者的巨大声响所吸引,而忽略了主任对该家庭重要的背景介绍,连主任都忍无可忍了

不仅观众被这个搅局者的巨大声响所吸引,而忽略了主任对该家庭重要的背景介绍,连主任都忍无可忍了 我再干正事,你在旁边瞎搅和,但是老太太说她也只是在干正事,不能为此而丢掉自己的工作

我再干正事,你在旁边瞎搅和,但是老太太说她也只是在干正事,不能为此而丢掉自己的工作那么对于主任呢?他也是在干正事,他如此认真也是为了遗孤能找到一个真正合适的领养家庭,他们都是做着自己的分内事。

主任说出了自己的内心话,他也和之后的男主一样是犯过错的人,他内心也在煎熬,不想再犯错

主任说出了自己的内心话,他也和之后的男主一样是犯过错的人,他内心也在煎熬,不想再犯错所以老太太的出场是否有意义?不是多余的吧?

那么我说本片的形式影思是:任何人都需要对自己做的事负责,不管他受到了多大的外界的干扰。

是不是完全没问题了?

本片的实体影思是:1950年初麦卡锡主义开始泛滥,知识分子应该不受外界干扰做对得起自己良心和责任的事情。

也许你不同意我的观点,但战后思潮就是这样。

Possibly the only female director working under the stricture of studio system of Hollywood’s Golden Age, actress-turned-moviemaker Ida Lupino has two pictures released in 1953 (soon her production company would close up shop and she would only direct one more picture in 1965), both grittily tackles the thorny, contentious maladies of American society at large.

THE BIGAMIST is a moral conundrum, San Franciscan couple Harry Graham (O’Brien) and Eve’s (Fontaine) conjugal harmony begins to crumble after they they find out Eve is infertile, turning her disappointment into business-driving entrepreneurship, Eve distances both emotionally and physically from Harry, who feels excruciatingly lonesome when on his business days in L.A, where he meets Phyllis Martin (Lupino), a waitress he finds rather sympathetic.

Collier Young’s script (yes, he is also the producer, Lupino’s ex-husband and Fontaine’s current hubby, talking about in-jokes and self-reference!) eminently portrays Phyllis as an independent-thinking, no-string-attached sweetheart that even a decent man like Harry cannot resist her blunt, unsentimental spell, “I don’t want anything from you.” is Phyllis’ opening remark. Therefore, in order to validate that Harry and Phyllis’ reluctant union (after Phyllis has a bun in the oven) is out of unalloyed mutual love, Eve has to take the short stick on account of her distancing maneuvers, sheer insouciance when Harry mentionsto her his first encounter with Phyllis on a Hollywood tour bus. Eventually, it is Eve’s belated decision to adopt a baby that puts Harry’s double life on a line, when a diligent adoption agent Mr. Jordan (Gwenn) is keen on getting to the bottom of it.

While the narrative gains on a typical melodrama, Lupino the director refrains from performative hyperbole and swelling music to elicit audience’s sensorial response, instead she adopts a matter-of-fact tenet to map onto the triad’s mental trajectories with admirable exactitude, with O’Brien strenuously carrying off Harry’s beset disquietude and Lupino herself, playing pitch-perfect notes of Phyllis’ fragile brave face. THE BIGAMIST is a searing drama but its intensity is not exterior but interior.

THE HITCH-HIKER, released 9 months before THE BIGAMIST, is a taut all-hombre film-noir based on the lurid true story of a psychopathic hitch-hiker on a killing spree, a polarized remove from Lupino’s woman-issue B pictures she has cranked out since 1949.

Two ordinary men Roy Collins and Gilbert Bowen (O’Brien and Lovejoy) are heading to a fishing trip in Mexico, but incur a hostage to fortune after picking up Emmett Myers (Talman), who, at the drop of a hat, points a pistol at them. Coerced to do Myers’ bidding, the two friends come in for psychological and physical torment while they traverse through the expansive, often barren terrain in the heart of the Baja California Peninsula (Lupino and her team make great play of extensive location shootings that renders the pair’s noir-ish nightmare melt under the sweltering sun).

Talman, with one “bum eye” whose eyelid cannot be closed on a chilling, odiously smug mug, makes for an excellent villain and unregenerately spouts Myers’ venomous affronts one after another, letting his baseness and slyness get the better of the hapless duo, who are the essential salt-of-the-earth type, driven to crack under mounting pressure (O’Brien’s Collins is the one who almost loses it and Lovejoy’s Bowne is more resilient, patient and astute).

If Lupino really enters into the spirit by building up the tension and confrontation, THE HITCH-HIKER’s finale somewhat sags when the inevitable comeuppance transpires patly, elicits a bathetic feeling, why the heck they couldn’t act sooner to end their protracted misery?

Showing her laudable proficiency in molding two disparate pictures, Lupino’s singular case only woefully reminds us gender is never an issue in movie business’ division of labor. Ergo today, collectively and unflaggingly we should welcome women and members of the minorities into all the tiers of the moviemaking edifice, just for the sake of putting it to rights, since the century-long accumulated debts are plain outrageous.

referential entries: Byron Haskin’s TOO LATE FOR TEARS (1949, 6.7/10); Alfred Hitchcock’s SUSPICION (1941, 7.6/10).